GRAFT | MoCP

Puerto Rico’s legal status as an unincorporated territory of the United States has long been a source of both confusion and contention. A former Spanish colony ceded to the United States during the Spanish-American War, the island has been subjected to a benign form of colonialism even after its people were granted American citizenship in 1917.1 Throughout the twentieth century, separatist movements often had to face top-down legislation aimed at coercing Puerto Rican assimilation. Even the 1952 constitution labeled the island an Estado Libre Asociado, which officially translates as a free associated state or “Commonwealth”— underscoring the island’s statelessness.

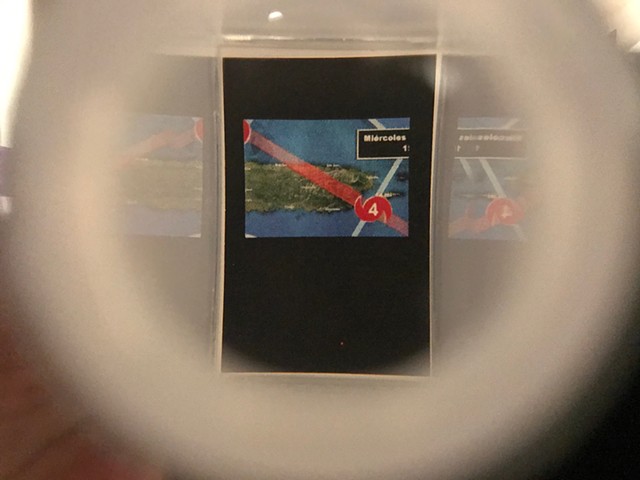

In the past four years, a tumultuous chain of events has further strained Puerto Rico’s relationship with the United States, causing a surge in mainstream news coverage outside the island.2 The summer of 2016 marked a significant moment in Puerto Rico’s contemporary history with the passing of the US federal law known as the Puerto Rican Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA). Enacted to oversee the Puerto Rican government-debt crisis, the law has resulted in detrimental cuts to the island’s public services. Severe austerity measures have made it impossible to address the island’s crumbling infrastructure, as the local economy’s second decade of recession has left the island vulnerable to further crises, particularly Hurricane María in September 2017. In the aftermath of the hurricane, Puerto Rico’s population winnowed by several thousand untallied deaths and the ensuing exodus of many more residents. In July 2019, the island erupted in protest. While the primary issue was the corruption of the island’s governor, the protests were the result of long-simmering frustrations with the status quo.

In American media, Puerto Rico is seldom discussed outside of these flashpoint political events. Ongoing crises that affect the island on a daily basis receive minimal coverage, and Puerto Ricans are often left to tell their stories only to one another. In the United States, images of their struggles occasionally permeate the news—photographs of disaster, desperation, and moments of fleeting triumph. With the narrative properties of visual news media in mind, Temporal explores a cultural reclaiming of storytelling through image and photojournalist practices. The exhibition’s title Temporal is not solely a reference to the temporalities of the photographic image, news cycles, and colonialism. In Spanish, temporal also translates to storm, suggesting not just a literal hurricane, but the inevitability of a popular upswell of anti-government sentiment. Puerto Ricans will also recognize the term temporal from a Puerto Rican folk song of the same name, popularized in the musical form of plena. Plena has been referred to as the “sung newspaper” of the people, telling the stories and gossip of the barrios through song. Percussive and mobile due to the use of hand drums, it is used in contemporary protest movements to communicate the Puerto Rican people’s most pressing social issues—violence against women, government corruption, and looming disasters, natural or humanmade—while providing a rhythmic format where all of these grievances can come together as a harmonious medley. Temporal is thus organized with this format in mind, with these same issues that are often woven into traditional plena songs. As musician and historian Ramón López states: “Plena is alive and present in daily puertoricanness because it expresses the communal memory that ties together history and actuality.

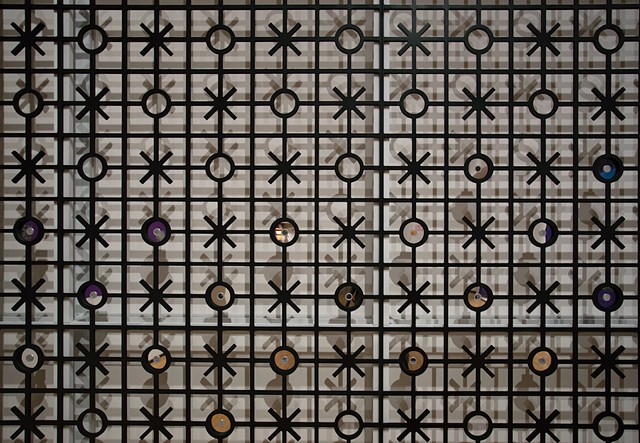

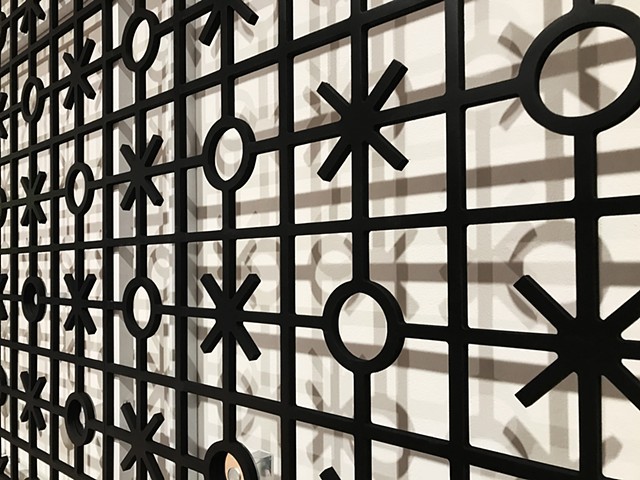

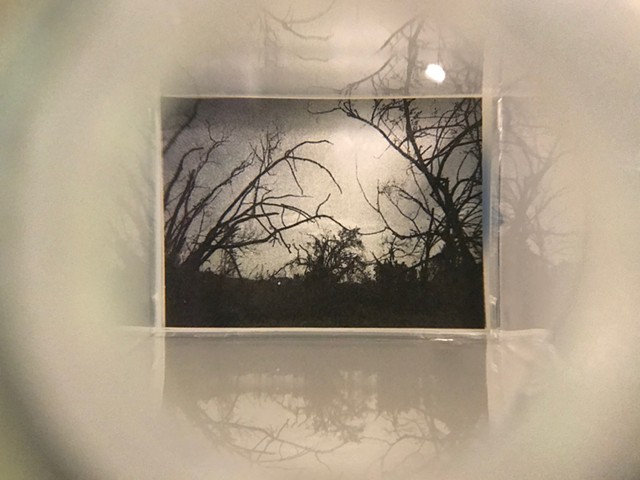

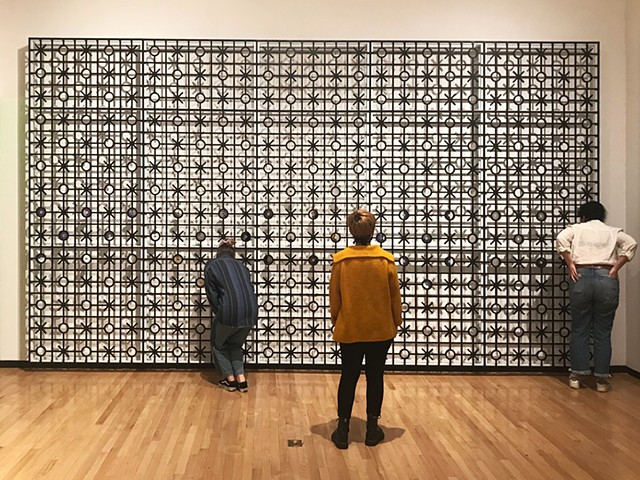

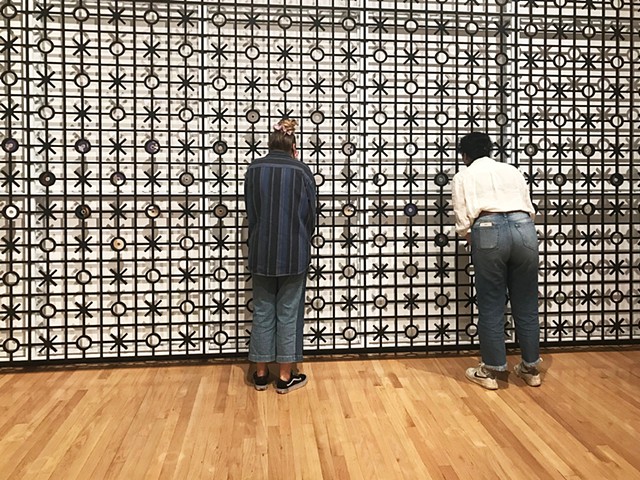

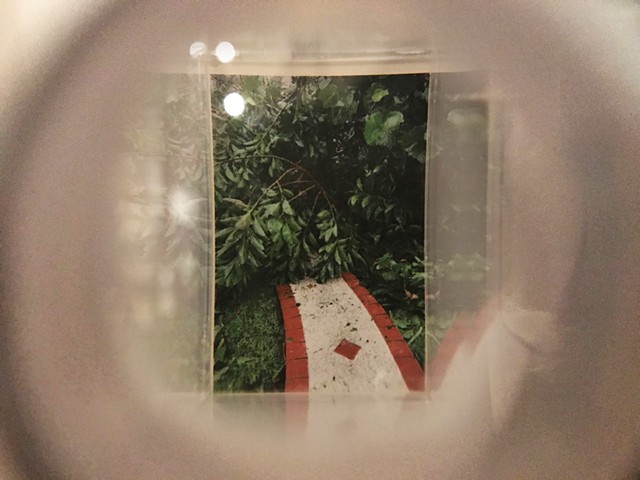

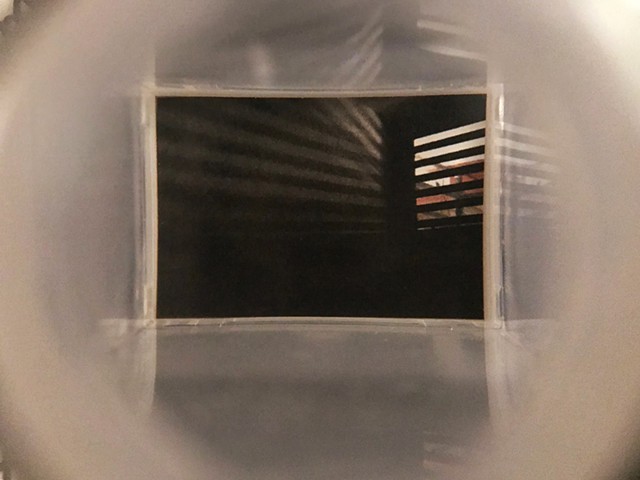

In the exhibition, works by eleven contemporary artists and photojournalists explore these interconnected sociopolitical issues. Interdisciplinary artist Edra Soto (Puerto Rican, b. 1971) showcases a new iteration of her ongoing project GRAFT, an intervention of vernacular architecture modeled after quiebrasoles (ornamental concrete blocks that provide shade from the sun) and rejas (wrought iron screens that serve as protective barriers on homes) used prominently on the island. The work becomes photographic with her insertion of viewfinders embedded in the structure that reveal images she has taken while in Puerto Rico, including immediately following the passage of María.

Read the full essay in english by Dalina Aimée Perdomo Álvarez

Curatorial Fellow for Diversity in the Arts:

www.mocp.org/education/resources/tempor…

In Spanish:

www.mocp.org/education/resources/tempor…